Democratize Healthcare.Expertly.

By Elaine Blechman, CEO of Prosocial Applications and Professor Emerita U. of Colorado

The success of fintech in democratizing finance1 so financial services are “friendly, approachable and understandable for newcomers and experts alike”2 offers hope that healthtech can democratize healthcare3 empowering every person to claw back satisfying outcomes from the high-cost, low quality U.S. healthcare4 system. Fintech democratizes when it is consumer-controlled, sidestepping technology that enables corporate referrees—banks and brokers—to control the data and wealth of individuals. Healthtech will democratize when it too is consumer-controlled, sidestepping wellness apps and patient portals with which corporate referees—employers, health plans and healthcare organizations—control the data and health of individuals.

The COVID-19 pandemic5 revealed the risks of our fractured healthcare system for all but the wealthiest and the need for top-down structural reform6. Meanwhile, the rest of us need a new bottom-up kind of healthtech, controlled by patients and family caregivers not by the private and public entities who employ, insure, and manage healthcare services and products. We need consumer-controlled healthtech that saves us time on system navigation7 to spend on healthy behavior and engagement with trusted healthcare providers.

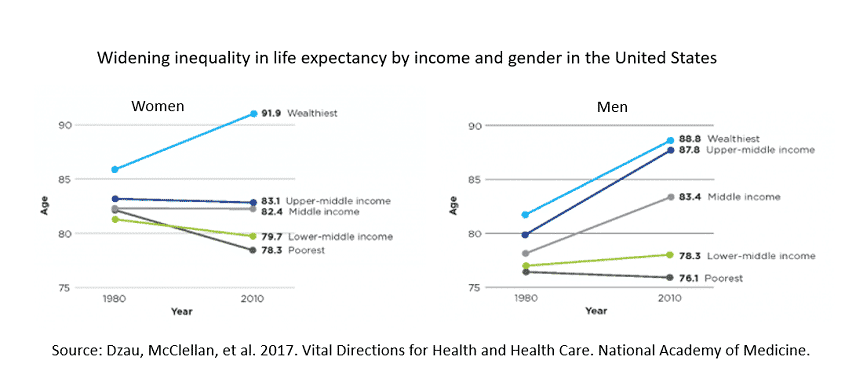

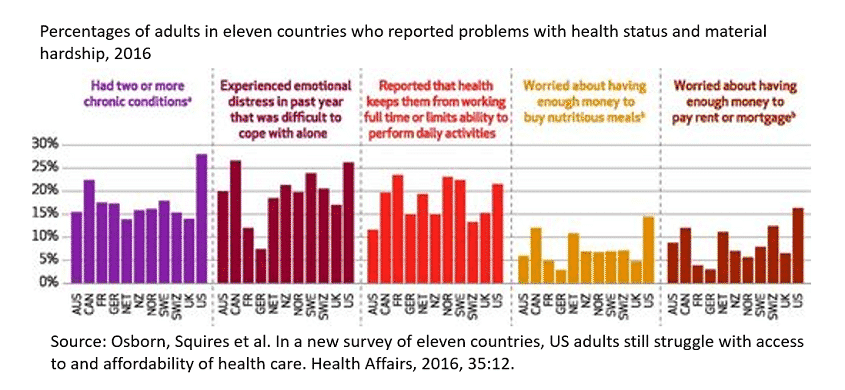

Higher prices8 explain why the US spends nearly twice as much on healthcare compared to other high-income countries. Comparatively less US spending per capita on resources (hospital beds, physicians, nurses) and skewed allocation of resources to high-income communities may explain why the COVID-19 pandemic cut US life expectancy9 during the first half of 2020 by one year for White-, two for Hispanic- and three for Black-Americans. Higher prices and scarce resources may explain why life expectancy10 is longer than 20 years ago for high-income men and women, unchanged for low-income males, and declining for low-income women. Why chronic health conditions11 are overrepresented among U.S. adults (28%). And why older people12 covered by Medicare cannot afford necessary care.

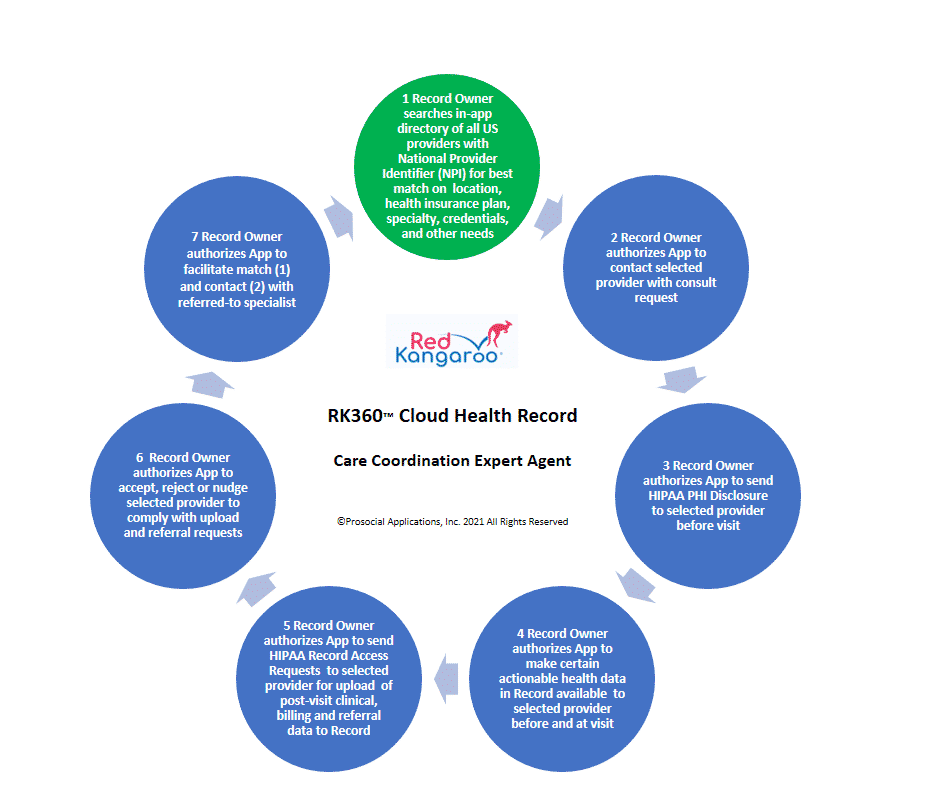

The RK360® Cloud Health Record App implements the consumer-controlled healthtech mission by enabling users to be more efficient and productive when navigating the healthcare system regardless of gender, health, income, old age, or race. The versatile RK360® App lets users choose among tasks related to system navigation, care engagement and healthy behavior that suit their current needs. Corresponding to each task is an expert AI agent, with an algorithm that leverages the knowledge and reasoning of domain experts.

A key system navigation task involves coordination of patient care13 across providers and time in order to avoid medical errors14 and surprise bills15. Before each telehealth or onsite healthcare visit, the RK360® App user taps a few buttons to activate the care-coordination expert agent for RK360® App follow through on a care-coordination cycle of subtasks. During each cycle, the RK360® App communicates patient requests under applicable federal and state laws and evidence-based practice standards and offers providers tools for complying with those requests and receiving documentation of their compliance.

Without the RK360® App, consumers can spend countless hours on the phone and in person trying to coordinate care for primary care, diagnostic workup, specialist consult, follow up, and care transition visits. With the App, consumers let the RK360® Care-Coordination Agent do the heavy lifting.

Consumers capture, own, and control their multi-source, multi-type, immutable clinical and financial data in a two-factor-authenticated cloud health record and do the same for family members for whom they make healthcare decisions and serve as HIPAA personal representative16. All without knowing much about record access rights17 under HIPAA and 21st Century Cures rules18.

Consumers drive exchange of immutable contents of cloud records (and those of family members they represent) with high-tech providers via interoperable electronic health record systems (EHRs) and with low-tech providers via two-factor authenticated web portals. All without knowing much about industry technical standards19 or government regulations20 for interoperability21.

Consumers own and control for clinical purposes all personally identifiable radiology images, genomic profiles, patient-reported outcomes and other immutable data in their (and their family members’) longitudinal cloud records and can choose to profit from leasing deidentified data for research. All without knowing much about “the new currency” 22 involving patient data ownership23 for big data.

The RK360® App is for people like Keira a 45-year-old bookkeeper and cancer survivor who makes health care decisions for herself, her husband with MS, her special-needs teenage son, and her elderly parents. Keira is a fictitious persona representing one in five Americans who are unpaid family caregivers24. Her family resembles 45% of nonelderly U.S. families25 with at least one chronically ill member. She wants an app that makes care coordination more efficient26, saving time for walks with her husband and bike rides with her son.

We recognize and appreciate the risks of COVID-19 to healthcare workers27 and their families as well as their knowledge of what consumers need. If you are a healthcare worker with an individual or organizational National Provider Identifier (NPI), subscribe to no-cost beta test RK360® Cloud Health Records for yourself and your family. Beta-testers retain their no-cost annual RK360® subscriptions, valued at $120, as long as they frequently use their RK360® Records.

References

1 Schulman, D. & Kirkland, R. (2017, March 7). Using fintech to democratize financial services. McKinsey & Company. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/financial-services/our-insights/using-fintech-to-democratize-financial-services

2 Robinhood. (2021, March 18)

3 Tang, P. C., Smith, M. D., Adler-Milstein, J., Delbanco, T., Downs, S. J., Mallya, G. G., Ness, D. L., Parker, R. M. & Sands, D. Z. 2016. The Democratization of Health Care: A Vital Direction for Health and Health Care. NAM Perspectives. Discussion Paper, National Academy of Medicine, Washington, DC. https://doi.org/10.31478/201609s

4 Stanford Medicine. (2018, December). 2018 Health Trends Report: The Democratization of Healthcare. https://med.stanford.edu/content/dam/sm/school/documents/Health-Trends-Report/Stanford-Medicine-Health-Trends-Report-2018.pdf

5 Gates, B. (2020, April 30). Responding to Covid-19—A Once-in-a Century Pandemic? New England Journal of Medicine, (382), 1677-1679. https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/nejmp2003762

6 Blumenthal, D., Fowler, E.J., Abrams, M., & Collins, S.R. Covid-19 — Implications for the Health Care System. (2020, October 8). New England Journal of Medicine, (383), 1483-1488. https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/nejmsb2021088

7 Corbett, C. M., Somers, T. J., Nuñez, C. M., Majestic, C. M., Shelby, R. A., Worthy, V. C., Barrett, N. J., & Patierno, S. R. (2020). Evolution of a longitudinal, multidisciplinary, and scalable patient navigation matrix model. Cancer Medicine, 9(9), 3202–3210. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/cam4.2950

8 Anderson, G. F., Hussey, P., & Petrosyan, V. (2019). It’s Still the Prices, Stupid: Why the US Spends So Much on Health Care, and a Tribute to Uwe Reinhardt. Health Affairs (Project Hope), 38(1), 87–95. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05144

9 Arias, E., Tejada-Vera, B., & Ahmad, F. (2021, February). Provisional life expectancy estimates for January through June 2020. Vital Statistics Rapid Release, (10). Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/vsrr/VSRR10-508.pdf

10 Dzau, V. J., McClellan, M., Burke, S., Coye, M. J., Daschle, T. A., Diaz, A., Frist, W. H., Gaines, M. E., Hamburg, M. A., Henney, J.E., Kumanyika, S., Leavitt, M. O., McGinnis, J. M., Parker, R., Sandy, L. G., Schaeffer, L. D., Steele, P. T. & Zerhouni, E. 2017. Vital Directions for Health and Health Care: Priorities from a National Academy of Medicine Initiative. NAM Perspectives. Discussion Paper, National Academy of Medicine, Washington, DC. https://doi.org/10.31478/201703e

11 Osborn, R., Squires, D., Doty, M. M., Sarnak, D. O., & Schneider, E. C. (2016). In New Survey of Eleven Countries, US Adults Still Struggle with Access to and Affordability of Health Care. Health Affairs (Project Hope), 35(12), 2327–2336. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1088

12 Osborn, R., Doty, M. M., Moulds, D., Sarnak, D. O., & Shah, A. (2017). Older Americans Were Sicker and Faced More Financial Barriers to Health Care than Counterparts in Other Countries. Health Affairs (Project Hope), 36(12), 2123–2132. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1048

13 Walton, H., Hudson, E., Simpson, A., Ramsay, A., Kai, J., Morris, S., Sutcliffe, A. G., & Fulop, N. J. (2020). Defining Coordinated Care for People with Rare Conditions: A Scoping Review. International journal of integrated care, 20(2), 14. https://doi.org/10.5334/ijic.5464

14 Anderson, J. G., & Abrahamson, K. (2017). Your Health Care May Kill You: Medical Errors. Studies in health technology and informatics, 234, 13–17. PMID: 28186008. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28186008/#:~:text=Recent%20studies%20of%20medical%20errors,third%20leading%20cause%20of%20death

15 Kaiser Family Foundation. (2021, February 4). Surprise Medical Bills: New Protections for Consumers Take Effect in 2022. https://www.kff.org/private-insurance/fact-sheet/surprise-medical-bills-new-protections-for-consumers-take-effect-in-2022

16 U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. (2021, March 18). Personal Representatives. 45 CFR 164.502(g). https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/privacy/guidance/personal-representatives/index.html

17 U.S. Government Accountability Office. GAO. (2018, May). Report to Congressional Committees. Medical Records. Fees and challenges associated with patients’ access. GAO-18-386. https://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-18-386

18 Morgan, S., & Moriarty, L. (2021, March 18). 21st Century Cures Act & the HIPAA Access Right. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Office for Civil Rights. https://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/2018-12/LeveragingHITtoPromotePatientAccess2.pdf

19 HL7 International. (2021, March 18). Introducing HL7 FHIR. https://www.hl7.org/fhir/summary.html

20 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (2021, March 18). Policies and Technology for Interoperability and Burden Reduction. https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Interoperability/index

21 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. (2021, March 18). ONC’s Cures Act Final Rule. https://www.healthit.gov/topic/information-blocking

22 Eggers, W.D., Hammil, R., & Ali, A. (2013, July 24). Data as the New Currency. Deloitte Insights.

23 Mirchev, M., Mircheva, I., & Kerekovska, A. (2020). The Academic Viewpoint on Patient Data Ownership in the Context of Big Data: Scoping Review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22 (8), e22214. https://doi.org/10.2196/22214

24 National Alliance for Caregiving. (2020, May). Caregiving in the U.S. 2020 Report. https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/ppi/2020/05/full-report-caregiving-in-the-united-states.doi.10.26419-2Fppi.00103.001.pdf

25 Claxton G, Cox C, Damico LL, Politz K. (2019, October 4). Pre-existing condition prevalence for individuals and families. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/health-reform/issue-brief/pre-existing-condition-prevalence-for-individuals-and-families/

26 Pew Charitable Trust. (2020, March 17). Patients Seek Better Exchange of Health Data Among Their Care Providers. Focus groups highlight issues that new federal regulations aim to address. https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/issue-briefs/2020/03/patients-seek-better-exchange-of-health-data-among-their-care-providers

27 Driggin, E., Madhavan, M. V., Bikdeli, B., Chuich, T., Laracy, J., Biondi-Zoccai, G., Brown, T. S., Der Nigoghossian, C., Zidar, D. A., Haythe, J., Brodie, D., Beckman, J. A., Kirtane, A. J., Stone, G. W., Krumholz, H. M., & Parikh, S. A. (2020). Cardiovascular Considerations for Patients, Health Care Workers, and Health Systems During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 75(18), 2352–2371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2020.03.031

Elaine Blechman is CEO of Prosocial Applications and Professor Emerita U. of Colorado.

The information in this blog should not be used as a substitute for professional medical care or advice. You should contact your physician or other health professional for advice concerning a particular condition or concern.

Connecting Patients to Providers through Personalized Health Information